Ruth Ann Fredenthal at Stark

This exhibition consisted of four apparently monochromatic oils,

each about 5 feet square, plus a smaller oil of similar appearance.

The colors are muted, seemingly gray ranging to mauve, and the rough

oyster linen on which they are painted reflects the light slightly differently

depending on the visitor's angle of view and the amount of natural light in

the gallery. The works are unframed, and the canvas that bends over the

edge of the stretcher appears to be a somewhat different color, though this

may be an optical illusion.

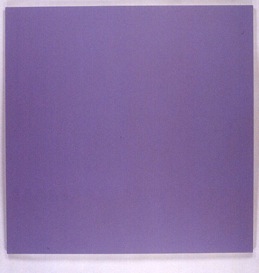

In fact, however, the paintings are not

monochromatic. Untitled #146, for example,

is horizontally divided roughly in half.

The top half is further subdivided into three

equal vertical bands of different colors,

while the bottom nail has two vertical bands.

The other paintings have similar divisions.

To speak of "bands,"though, is a misnomer,

as the colors are so close in hue as to be

almost indistinguishable. Moreover, the

dividing lines between the bands are not

straight; instead they swerve in and out like

jigsaw puzzle pieces, making it doubly difficult

to tell where one color ends and another begins.

Untitled 146, (1990-93), Multilayered oil on Oyster linen, 60" x 60", The Panza Collection

(Stanza del Camino - Villa Panza Museum, Varese, Italy)

(Photo: Larry Wheelock)

Fredenthal's brush stroke is very subtle as well, with no Impasto to define

boundaries. Such a description makes the works sound like a kind of optical test,

and there is that air to the viewing. It's like being asked to distinguish temperature

variations in a room in which one corner is kept at 70 degrees, another at 71

degrees and so on. With Fredenthal's paintings, the intense concentration

required to detect their Infinitesimal visual shifts gives the viewer a sense

of heightened awareness, of focusing on the very act of seeing.

These works definitely take time to view—appropriately so, as it took the artist

three years and more to make them In what spirit, I wonder, was the paint

applied to the canvas? In a Zen-like trance of "thereness"? With a matter-of-fact

knit-one, purl-two attitude? In any event, Fredenthal in these paintings

out-Reinhardts Ad Relnhardt. She's a painter's painter, with all that term Implies

of integrity of artistic investigation and of complexity in apparently simple

format. It takes a while to come to these works, and many will not feel compelled

to make the effort. But for those who persevere, the seduction is there.

—Reagan Upshaw

Ruth Ann Fredenthal at Vera Engelhorn

What you see is what you get in Ruth Ann Fredenthal's paintings, but what you see

is contingent upon now long you're willing to look. At first glance you're convinced

that you've come upon some rather low-voltage monochromatic canvases in muted

off-gray violets and blues. The hurried viewer, the one "making the rounds," might

leave it at that. Those fortunate few who were clued in beforehand, however, or

who happened to catch a hint of a strange animation in the paintings' color fields

and stuck around to gaze intently at the works, must have found this to be one of

the more rewarding shows of the fall season.

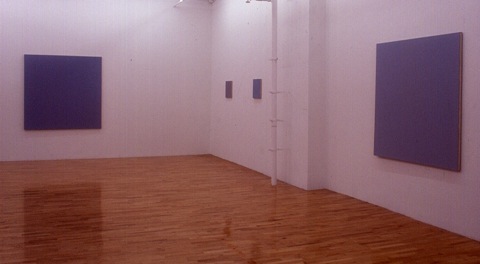

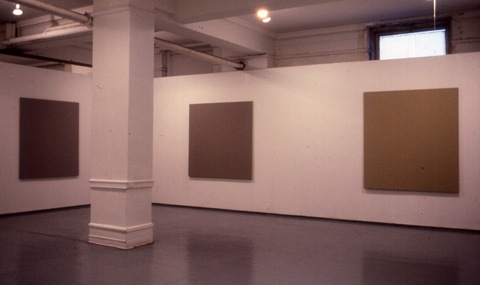

One Person Exhibition, 1989, Vera Engelhorn Gallery, SOHO, NYC (Photo: WoWe)

Large paintings from left to right:

Untitled 133 (1988-89), Multilayered oil on Oyster linen, 66" x 66", The Panza Collection

Untitled 130 (1987-88), Multilayered oil on Oyster linen, 60" x 60", The Panza Collection,

(Villa Panza Museum, Varese, Italy)

Fredenthal works with microtonalities of color, something akin to LaMonte Young's

music. If you look at her paintings long enough, you'll notice that their surfaces are

divided into staggered rows of interlocking planes that fit together along softly

rounded interlocking edges that resemble chains of jigsaw-puzzle pieces. The

regularity and repetition of this curvilinear tongue and groove reads as systematic

notation. And yet, even as you register the arithmetical structures organizing the

work, you become aware of another element or "voice," that of light-filled color.

As soon as you notice the difference in color temperature from one band to another,

the interlocking planes begin to declare their separate indentities as primary and

secondary hues. The gray panels open up into cloud banks of light.

One Person Exhibition, 1989, Vera Engelhorn Gallery, SOHO, NYC (Photo: WoWe)

This transformation takes place in painting after painting, yet it's never quite the same

and is always a surprise. Once you see the color divisions, the graphic and spatial

readings of each painting fire simultaneously. The works have a strong object-quality

as well. Because of the sidelong way their color is perceived—out of the corner of your

eye—the paintings appear to advance a bit from their physical surfaces. Op art

achieved something of this retinality, but it was much noisier about it and that one effect

was pretty much the end ot the story. In Fredenthal's work, by contrast, many ways of

seeing blossom forth from a modestly drab first impression. There is nothing inherently

spiritual or symbolic about these paintings, grounded as they are in the phenomenology

of the concrete, but I can envision a chapel setting for a series of them.

In their unobtrusive manner, they are miraculous.

—Stephen Westfall

Ruth Ann Fredenthal at the Clocktower

It is rare these days for an artist's first solo show to be a retrospective, but such was

the case with Ruth Ann Fredenthal's debut at the Clocktower. A colorist of long standing,

Fredenthal's work in this show spanned the period from 1973 to '80, years in which her

general structural and expressive goals remained the same, but particular compositions

and color concerns evolved.

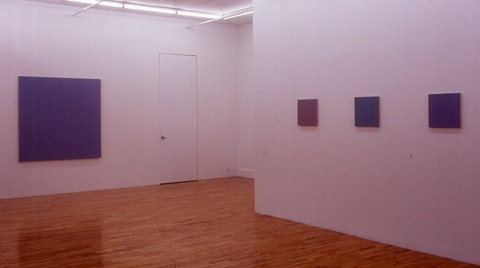

One Person Exhibition - 10 Year Retrospective, 1980, PS 1, (Photo: Erik Saxon)

Institute for Urban Resources, The Clocktower, NYC.

Paintings from left to right:

Untitled 48 (1976-77), Multilayered oil on Ulster, linen, 66" x 60", Private Collection, Italy

Untitled 70 (1978-79), Multilayered oil on Oyster linen, 66" x 66", The Panza Collection

Untitled 69 (1978-79), Multilayered oil on Oyster linen, 72" x 66"

Fredenthal's arena is the expressive and spiritual content of color. Each canvas comprises

a color she calls the "mass tone" of the painting, and one or more variations of that tone

produced by mixing it with tiny amounts of other hues. The canvases are square or nearly

so, divided simply into rectilinear sections. The sections join, as puzzle pieces do, with

curving, interlocking edges, so that the color sections seem to fit together naturally rather

than simply abut. In the earlier works, the curves themselves were large and assertive,

playful and almost imagistic. In works dating from the middle 70s and later, the curves

become very small in compass, occasionally less than two inches wide.

The regular, meandering curves of her jigsaw pieces reflect her debt to abstractionist Paul

Feeley, with whom she studied at Bennington College. (Fredenthal painted all his wooden

sculptures, and executed the large Sculpture Court piece shown at the Guggenheim after

his death). Though Fredenthal had painted curves before their meeting, it was he who led

her to clean them up and make them uniform.

One Person Exhibition - 10 Year Retrospective, 1980, PS 1, (Photo: Erik Saxon)

Institute for Urban Resources, The Clocktower, NYC

This curving, interlocking structure, however, is nearly invisible in Fredenthal's paintings.

After a few minutes of looking, the minuscule color differences among the sections of a

painting reach the threshold of perception. Most viewers perceive only a few of her carefully

painted joinings and only some of her color variations. Many leave thinking they have just

seen monochromes. Fredenthal is not overly disturbed by this; she's after the "whole" experience

of the colors, and emphasizes that the subdivisions are only part of the point. Her brush technique

offers virtually no evidence of touch, and the weave of the linen remains visible beneath the eight

or more coats of oil paint she habitually applies; this textural uniformity adds to the integrated feel

of the paintings.

Her colors evolve, in this show, from warm, sienna-based earth tones, resonant with ambers and

flesh colors, to warm and then cooler grays. The paintings, engulfing the viewer, serve as fields

for the eye's own dancing afterimages. Two of the latest paintings are a mauve gray and a steel

gray respectively, each with numerous but almost imperceptible subdivisions. No brushstroke gives

away the positions of her jigsaw joinings, and the intense gallery lights melt color differences away.

These paintings are to colors what chords are to music—complex wholes affected by but superior to

their individual components.

—Ellen Lubell